Fencing out Wildlife

December 27, 2022

Chain Link Fence, Tube and Fittings

January 24, 2023On the Fence: New Research Taps Rancher Expertise on Living With Carnivores

A well-designed fence can help to prevent conflicts with carnivores, but with so many options for material, placement and logistics, researchers can struggle to identify what strategies have the best chance for success. They turned to ranchers for help. (Photo Credit: Jan Canty/Unsplash)

They say that good fences make good neighbors — especially true when you share space with gray wolves and grizzly bears.

In places like Wyoming and Idaho, ranchers have learned practical fencing strategies to help to reduce ill-fated encounters between hungry wildlife, vulnerable livestock and valuable produce. USU researchers are learning to take advantage of this hard-won knowledge, according to new research.

“Research about wildlife fencing is often missing on-the-ground knowledge,” says Julie Young of the Department of Wildland Resources and Ecology Center in the Quinney College of Natural Resources. “We wanted to reduce the cost and social burden of living with recovering wildlife populations, but we needed rancher input to do that.”

Given all possible options for fencing material, placement and logistics, the team wanted to zero in on strategies that had the best chance for success. They turned to the ranchers who have worked for decades in the “trenches” of wildlife conflict to help.

Young organized a group that included livestock producers, natural resource managers and university-based researchers. They met for four months — early in the morning to accommodate producers’ crack-of-dawn schedules. Participants were exposed to the reality of fencing designs and considerations across different scales: from hobby farms to orchard and apiary protection, to large cow-calf operations. The researchers learned about regulatory implications and obstacles to fencing on certain rangelands, which informed how they thought about adoption and the practicality of their research.

Once the research project began to take shape, they took the plan back to the ranchers for feedback.

“Our original design looked just at the effectiveness of fencing designs for preventing conflicts with agriculture or livestock. Concerns about human safety was something we initially overlooked,” says Rae Nickerson, coauthor on the research and a Ph.D. student in the Department of Wildland Resources and Ecology Center.

But fencing projects are often located near homestead areas, the researchers learned, and human safety was an issue important to the group. “Some of the new things we learned from the process required flexibility in the process,” Nickerson says. “But it offered a unique way to prioritize our approach. It really took advantage of a diverse set of knowledge and experience.”

Researchers involved in creating preventative strategies for wildlife often view the issue from the perspective of the ecology of carnivores, but that’s not the sole priority of most producers. The researchers learned that they needed to integrate not just how and where fences were effective, but also how to make funding opportunities and paperwork more flexible for the producers. Ranching operations near increasing populations of large carnivores need information quickly, they said, before problems get out of control.

The group also planned strategies to get the word out about what ended up working, once the research was complete.

“Often the most promising and innovative tools aren’t circulated to managers and ranchers because they aren’t recorded or widely shared,” Young says. “The people who discover new and innovative tools to keep wildlife predators separate from livestock, grain storage and beehives often don’t have good ways to communicate their successes to others.”

Word-of-mouth can work, she says, but many of these folks are geographically separated from other producers confronted with the very same challenges. The team’s research will continue to look at the efficacy of using nonlethal tools to reduce wildlife conflicts and ways to disseminate best practices to more livestock owners.

Courtesy Quinney College of Natural Resources at Utah State University

Making Fences Friendlier for Ranchers and Wildlife

Mike Vickrey, a fifth-generation rancher in Pinedale, Wyoming, runs a cow-calf operation with his parents and daughters. The Vickreys’ rolling sagebrush pastures and hay fields sit east of the Wind River Mountains beside a tributary of the Green River. Along with the family’s 650 yearlings, the ranch’s high-elevation meadows support plentiful wildlife.

“We’ve got all the good stuff — elk, moose, antelope and sage grouse. Plus, we’re in the middle of the biggest mule deer migration corridor there is,” Vickrey says.

Lower top wires and higher bottom wires on this new ranch fence in Wyoming allow wildlife to safely travel over or under the wires. Photo by Jennifer Hayward, NRCS

Unfortunately, these animals can get injured or killed if caught in the ranch’s fences. Vickrey says he’s seen deer “hung up and twisted on the top wires.” So, when the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service began offering to help improve fences through its Environmental Quality Incentives Program, Vickrey seized the opportunity.

“It’s been a good way to replace old fences and get some new ones with less cost,” Vickery says. “The NRCS program lets us do more than we could have done on our own. Plus, it makes the landscape a little friendlier for animals to pass through.”

Since 2018, Vickrey has modified six miles of fence through EQIP in places where big game migrate each spring and winter. He’s also flagged fences with reflective markers in partnership with NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife to prevent sage grouse from getting tangled in the wires when they fly low to the ground. These fences still work well to keep cows contained, too.

Wildlife-friendly fence designs vary, but one common feature is that the top strand is lower than traditional woven-wire or five-strand barbed wire fences: 42 inches or less from the ground. “If the fence is too high, wildlife like mule deer have a difficult time navigating them, particularly after a long winter when their energy reserves are lower and especially pregnant females,” says Jennifer Hayward, NRCS district conservationist in Pinedale.

The bottom strand is also barbless and at least 16 inches above the ground. “Pronghorn [antelope] prefer to scoot under fences, so it’s important to have a smooth bottom wire that gives them plenty of space,” Hayward says.

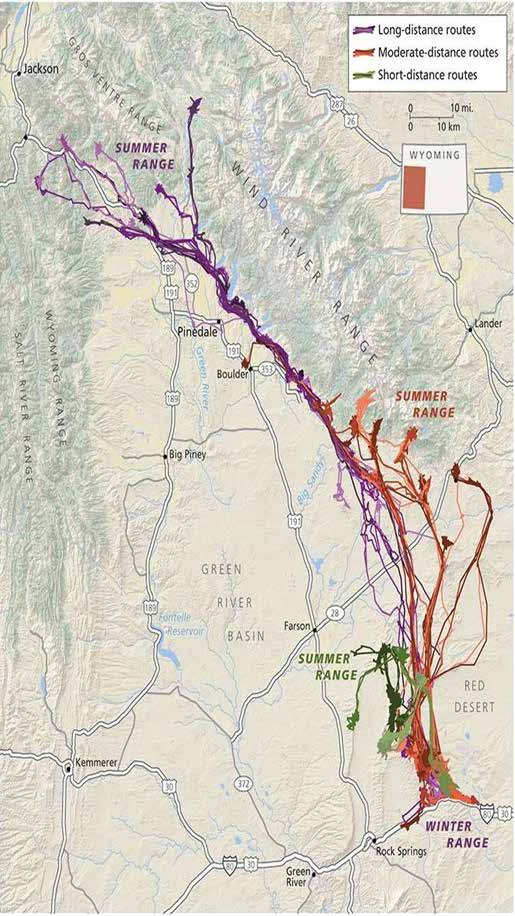

Research from GPS-collared animals helps pinpoint their migration routes. This map and many others from the Wyoming Migration Initiative help guide NRCS investments in modifying fences on private land.

by Brianna Randall for Natural Resources Conservation Service Working Lands for Wildlife. Reprinted with permission.

Hayward has worked with 30 landowners on fence modifications. She gives landowners a snapshot of how their fences are faring as part of a resource inventory provided with an NRCS conservation plan.

“Some of these fences are upwards of 75 years old, in need of repair or replacement. If one of those fences is also located on a migration route, it is eligible for cost-share to make it wildlife-friendly,” Hayward says.

NRCS has helped modify about 180 miles of fence in Sublette County where Vickrey has lived since 2017. Partners like The Nature Conservancy, the Sublette County Conservation District, and the U.S. Forest Service have completed an additional 100 miles. Cumulatively, these projects reduce injuries to wildlife moving along Wyoming’s “grass highway.”

Research from GPS-collared animals helps pinpoint their migration routes. This map and many others from the Wyoming Migration Initiative help guide NRCS investments in modifying fences on private land.

And, USDA is now committing additional resources to continue improving wildlife migration corridors as part of its recently announced Big Game Conservation Partnership, an initiative through NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife and the Farm Service Agency.

So far, Vickrey says he hasn’t found any wildlife hung up on his new fences, and they also keep his livestock where he wants them. He’s now partnering with the U.S. Forest Service to modify fences on public land where his family leases grazing allotments and the “elk are thick, thick, thick.”

“From our standpoint, we’re trying to carry on for another couple of generations, and we’d like to find a balance that makes it easier for wildlife,” Vickrey says. “I think most ranchers around here feel that way.” This guide provides tips on making fences wildlife friendly:

www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Wyo_

FenceGuide.pdf.

To find out more about wildlife conservation programs available to producers, visit: www.farmers.gov/wildlife.

Mike Vickrey, center, runs a ranch in southwest Wyoming with his parents, daughters and grandchildren. Photo courtesy Vickrey Family